Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Concerning the Spiritual in Art [Wassily Kandinsky, M. T. H. Sadler] on desertcart.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Concerning the Spiritual in Art Review: A must read for the artist of any medium - Take your time reading. If overwhelmed by the information, reread the last paragraph you read then put the book down. Mediate on those last read words. Simply think of that kernel of truth. Go on with your day or continue to read after digesting what you read. Don’t rush. The book has been in print longer than we have drawn breath. Enjoy the ideas, notice them in other media you see. Compare and contrast. Look up the artists he mentions if you aren’t familiar. This is a book to keep and go back to periodically. A treasure. The information, for the most part, has not dated itself out of usefulness. Quite the opposite. But keep in mind when it was written, the earliest part of last century. Abstract art isn’t the same art he witnessed or created. It is far more beautiful now than he probably ever thought it could be. Review: Kandinsky: Chaos, Order, and Meaning - I’ll have to say I feel like I have only gleaned the surface of Kandinsky’s meaning relative to the spiritual in art. What follows are some key themes that spoke to me: Art offers revolutionary possibility and is the sphere turned to in time of societal stress, breakdown, and chaos. “When religion, science and morality are shaken. . . . when the outer supports threaten to fall, man turns his gaze from externals in on to himself. Literature, music and art are the first and most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt” (p. 25). Artists and their art connects humans to a deeper or transcendent meaning. “To send light into the darkness of men’s hearts – such is the duty of the artist” (citing Schumann, p. 16). “No other power can take the place of art. . . at times when the human soul is gaining greater strength, art will grow in power, the two are inextricably connected” (p. 63). Art communicates – without the use of words. I’m increasingly tired of the primacy of words and speech acts as the preferred communication method – particularly when the rhetoric is 2D, hateful, and divisive. “At different points along the road are the different arts, saying what they are best able to say, and in the language (emphasis mine) which is peculiarly their own” (p. 31). One’s hermeneutic must move beyond impression or observation (what the art is, what it depicts, or its specific configuration or construction) to an allowance for the art to communicate its meaning. “Our materialistic age has produced a type of spectator or ‘connoisseur,’ who is not content to put himself opposite a picture and let it say its own message. Instead of allowing the inner value of the picture to work. . . . his eye does not probe the outer expression to arrive at the inner meaning” (p. 58). Kandinsky's Spiritual Triangle represents a societal and personal progression from solely material to spiritual concerns where the primary movement is influenced by artists and their work. “Painting is an art, and art is not vague production, transitory and isolated, but a power which be directed to the improvement and refinement of the human soul – to, in fact, the raising of the spiritual triangle” (p. 62). My curiosity about this notion of 'spiritual in art' arises from a bias that there's something about aesthetic experience that facilitates a moment where humans transcend individual interest solely captivated by the awe or beauty of the experience of art, music, theater, dance, etc. andinsky's work provides a framework via the triangle to understand art and artist's importance beyond the material toward meaning, purpose and transcendence. I realize in using the word transcendence I'm not defining it - this too is a term I want to learn more about. Reading Kandinsky is but a starting point in this exploration - finally, this work was written early in Kandinsky's career - it would be good to read more of his ideas to further clarify definition and meaning of key constructs: spiritual, sacred, inner meaning, and inner need, for examples. This would be a good read for those interested in art history, spirituality, aesthetics, and experience. I can imagine those interested in place design also benefiting from this book especially Kandinsky's discussion of color. Note: My review is based on 2010 version

| Best Sellers Rank | #27,038 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #21 in Arts & Photography Criticism #42 in Art History (Books) #1,061 in Classic Literature & Fiction |

| Customer Reviews | 4.4 4.4 out of 5 stars (740) |

| Dimensions | 5.43 x 0.2 x 8.54 inches |

| Edition | Revised |

| ISBN-10 | 0486234118 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0486234113 |

| Item Weight | 2.31 pounds |

| Language | English |

| Part of series | Dover Fine Art, History of Art |

| Print length | 96 pages |

| Publication date | June 1, 1977 |

| Publisher | Dover Publications |

M**N

A must read for the artist of any medium

Take your time reading. If overwhelmed by the information, reread the last paragraph you read then put the book down. Mediate on those last read words. Simply think of that kernel of truth. Go on with your day or continue to read after digesting what you read. Don’t rush. The book has been in print longer than we have drawn breath. Enjoy the ideas, notice them in other media you see. Compare and contrast. Look up the artists he mentions if you aren’t familiar. This is a book to keep and go back to periodically. A treasure. The information, for the most part, has not dated itself out of usefulness. Quite the opposite. But keep in mind when it was written, the earliest part of last century. Abstract art isn’t the same art he witnessed or created. It is far more beautiful now than he probably ever thought it could be.

A**N

Kandinsky: Chaos, Order, and Meaning

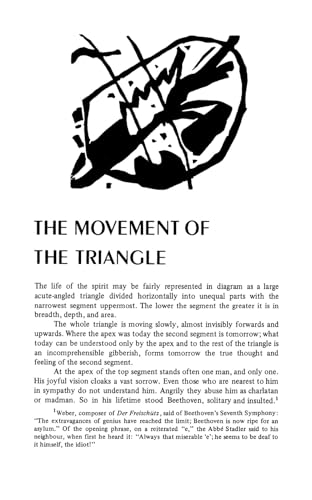

I’ll have to say I feel like I have only gleaned the surface of Kandinsky’s meaning relative to the spiritual in art. What follows are some key themes that spoke to me: Art offers revolutionary possibility and is the sphere turned to in time of societal stress, breakdown, and chaos. “When religion, science and morality are shaken. . . . when the outer supports threaten to fall, man turns his gaze from externals in on to himself. Literature, music and art are the first and most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt” (p. 25). Artists and their art connects humans to a deeper or transcendent meaning. “To send light into the darkness of men’s hearts – such is the duty of the artist” (citing Schumann, p. 16). “No other power can take the place of art. . . at times when the human soul is gaining greater strength, art will grow in power, the two are inextricably connected” (p. 63). Art communicates – without the use of words. I’m increasingly tired of the primacy of words and speech acts as the preferred communication method – particularly when the rhetoric is 2D, hateful, and divisive. “At different points along the road are the different arts, saying what they are best able to say, and in the language (emphasis mine) which is peculiarly their own” (p. 31). One’s hermeneutic must move beyond impression or observation (what the art is, what it depicts, or its specific configuration or construction) to an allowance for the art to communicate its meaning. “Our materialistic age has produced a type of spectator or ‘connoisseur,’ who is not content to put himself opposite a picture and let it say its own message. Instead of allowing the inner value of the picture to work. . . . his eye does not probe the outer expression to arrive at the inner meaning” (p. 58). Kandinsky's Spiritual Triangle represents a societal and personal progression from solely material to spiritual concerns where the primary movement is influenced by artists and their work. “Painting is an art, and art is not vague production, transitory and isolated, but a power which be directed to the improvement and refinement of the human soul – to, in fact, the raising of the spiritual triangle” (p. 62). My curiosity about this notion of 'spiritual in art' arises from a bias that there's something about aesthetic experience that facilitates a moment where humans transcend individual interest solely captivated by the awe or beauty of the experience of art, music, theater, dance, etc. andinsky's work provides a framework via the triangle to understand art and artist's importance beyond the material toward meaning, purpose and transcendence. I realize in using the word transcendence I'm not defining it - this too is a term I want to learn more about. Reading Kandinsky is but a starting point in this exploration - finally, this work was written early in Kandinsky's career - it would be good to read more of his ideas to further clarify definition and meaning of key constructs: spiritual, sacred, inner meaning, and inner need, for examples. This would be a good read for those interested in art history, spirituality, aesthetics, and experience. I can imagine those interested in place design also benefiting from this book especially Kandinsky's discussion of color. Note: My review is based on 2010 version

A**R

great depth though difficult read

Would be happy to read it again and again to grasp the essence of ideas from Kandinsky, the master of abstract.

S**E

Revisting, remembering, reliving

Any body and anybody is creative, some have a quasi innate ability to this others have to walk and work their way through the process more arduously. I wish we would have read Mr Kandinsky along side our exploration of his compositions during art lessons. It would would have provided a better understanding of the artistic process even though you think it outdated, and yet it ain’t.

G**N

Kandinsky Classic

I wanted to read this to find out what one of the innovators of abstraction thought about it enough to try to inform the rest of us. Comparing it to music works for me, but now there are Many Types of music when I'm sure he was talking about Classical Music. Some plan everything, but others just "let it fly." Why have rules for structure like some kind of code to decypher when expression doesn't have to mean anything unless the viewer wants it to? At the time he wrote this it all made perfect sense, and there are good pieces of information on color and composition, but if you're on "some brazen frontier light years from home" nothing has as much weight as what happens in that moment. In the infancy of abstraction there was an emphasis on making sense of it. 100 years later, that STILL works, but it's a bigger Universe with many examples he wasn't aware of, where there's Spirituality in just being there with your eyes open and paying attention. This is where you make your own rules.

R**E

Love This Artist, But Not My Favorite Piece of Writing

I found this book hard to follow and rarely convincing. The tone and content of the book strike me as unproductively self-interested, an imaginative exploration of the artist’s own values and aesthetic. This book does not take time defending itself. It bounces rapidly from one claim to the next. It’s hard to even capture what this book is about… in some areas it feels like a mystical version of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In other places it reminded me of a “sloppy Merleau-Ponty” -- the author has a lot of attractive ideas about the intersection of color and human perception/identity, but none of them are presented seriously. Overall, I found the book messy and forgettable.

M**T

A Classic for Any Creative

Considering the period in which this was written, an enlightening and insightful read for anyone involved with visual arts. Kandinsky's acute philosophical instincts offer readers a path to create deeper and more meaningful work.

S**B

Amo a Kandinsky, verdadero teórico del arte

A**H

This is a fantastic short book. I am amazed I hadn't heard of it before. It only came to my attention recently when one of my students, Nic Green, used it as a basis for her essay at the Centre for Human Ecology: the student teaching the teacher. Kandinsky, who was one of the founders of modern art, sets out to confront the crass materialism of his era. In this, he stands in the tradition of Russian art that sees "Art as service" - and specifically, as service of that which has the sacred at its core. He understands "spirituality" as being the interiority of things, their inner source of meaning and life. This leads to his attack on artistic narcissism, saying, "This neglect of inner meanings, which is the life of colours, this vain squandering of artistic power is called 'art for art's sake'." (p. 3). It needs to be understood that the cultural backdrop to this was that Russian intellectual life had been split by half a century of "positivism" coming in from the West - the materialistic idea that only "facts" matter, "the triumph of the fact", and that there is, as the positivists would have it, no God, therefore no soul, thus their nihilism. Just as writers at the time such as Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy attacked positivism in their novels, so a number of late 19th century Russian painters did so in their art - see From Russia: French and Russian Master Paintings 1870-1925: from Moscow and St Petersburg . One of the most influential, Ivan Kramskoi, was an initiator of The Wanderers (or Itinerants) circle, in Russian, the Peredvizhniki. As he put it, "What is a real atheist? He is a person who draws strength only from himself" (ibid. p. 164). In other words, a person with only their ego to ground their being in; thus the narcissism. Kandinsky was therefore not unique in his views. He was part of a wider movement of pre-WW1 art, an era resonant with the observation that "Attention to religion is always heightened in Russian art during times of cataclysm" (ibid. p. 167). What is special about Kandinsky's thoughts on the matter is that he has left us this book, translated into English, in which the need for art to be spiritually grounded is very clearly expressed. Consistent with his Russian Orthodox background he says, "We are seeking today for the road which is to lead us away from the outer to the inner basis. The spirit, like the body, can be strengthened and developed by frequent exercise. Just as the body, if neglected, grows weaker and finally impotent, so the spirit perishes if untended. And for this reason it is necessary for the artist to know the starting point for the exercise of his spirit. The starting point is the study of colour and its effects on men." (pp. 35-6). And I love his honesty in a footnote where he says, of his colour schema, "These statements have no scientific basis, but are founded purely on spiritual experience." (p. 37). Too often people who see spiritual qualities confuse these with scientific ones and therefore, in philosophical terms, make a category error which results in a sense of "misplaced concreteness" that, ultimately, profanes the spiritual. Kandinsky's honesty avoids this ... at least, he does so in the footnote though as we shall see, he may have been less successful in his conclusion. Art's function is therefore to reveal the spiritual. It "must learn from music that every harmony and every discord which springs from the inner spirit is beautiful, but that it is essential that they spring from the inner spirit and from that alone." (p. 51). This has a social function, for "each period of culture produces an art of its own which can never be repeated" (p. 1). As such, "Painting is an art, and art is not vague production, transitory and isolated, but a power which must be directed to the improvement and refinement of the human soul." (p. 54). Ultimately, "If the artist be priest of beauty", then s/he has, Kandinsky spells out, "a triple responsibility to the non-artist: (1) He must repay the talent which he has; (2) his deeds, feelings, and thoughts, as those of every man, create a spiritual atmosphere which is either pure or poisonous. (3) These deeds and thoughts are materials for his creations, which themselves exercise influence on the spiritual atmosphere. The artist is not only as king, as Peladan says, because he has great power, but also because he has great duties." (pp. 54-55). And the bottom line? "That is beautiful which is produced by the inner need, which springs from the soul." He concludes: "this property of the soul is the oil which facilitates the slow, scarcely visible but irresistible movement of [the human condition] onwards and upwards." As will be apparent, this sense of spiritual progress is certainly premodern (consistent, for example, with the "modes of vision" of Richard of St Victor, a medieval Scottish scholastic theologian). And it may be modern thinking inasmuch as the idea of progress is pronounced. But it is decidedly not postmodern. How interesting, therefore, that Kandinsky is seen as a progenitor of "modern" art and its seamless, to my eye, drift into the inchoate abstractions of postmodernity so apparent in his own later work. It is here that my criticism of Kandinsky must cut in. Kandinsky's mindset is, at the same time, premodern in its perception of the spiritual essence, but postmodernly deconstructive in the trend of its artistic expression. His work moves from the fairy-tale-like motifs of "Sunday: Old Russia" (1904) or "Song of the Volga" (1906), or Imatra (1917), into "First Abstraction" (1910) which is, well, pretty abstract, "Composition VII" (1913) which is also abstract but retains the richly iconic colouring for which he is famous, into the geometric near-nihilism of some of his later work - for example, "Descent" (1925) or "Development in Brown" (1933). What might we see as having happened here? My theory is that it has to do with the distinction between transcendent and immanent spirituality. Transcendent spirituality is about the divine beyond this world. Immanent spirituality is about God present in the world, including in its suffering as the "suffering God" (Moltmann). Immanent spirituality does not deny the transcendent, but sees it as also being "incarnate" - or enfleshed in this world. It seems to me judging from this little book that Kandinsky's views were transcendent. For example, he lacks the social realism of the Wanderers who sought to draw out the embodied beauty and integrity of the ordinary people. His aims are wonderful in seeking to make visible the spiritual as a prophetic action "towards the close of our already dying epoch" (p. 47). But the problem is with how he does this - by transcendence, thus an increasing abstraction and separation from the mundane world. Here we must be fair to Kandinsky and acknowledge that immanent theologies, such as in liberation theology or what Jurgen Moltman developed out of his WW2 prison camp experience, and which has always been present in eastern religions, were not well developed in the early 20th century. The Wanderers might be seen as a push towards immanence as when Kramskoi was one of the leaders who led the "revolt of fourteen" art students out of the Academy of Fine Arts in protest at church and state control over what constituted art, but Kandinsky does not seem to have followed this people's grounding in his spirituality. The result, in my view, is that such transcendent spirituality, abstracted from the immanent, progressively unhinges itself. It also has the unintended consequence of profaning the immanent, the material world, because incarnation no longer quickens it. Kandinsky calls this dematerialisation. He says, "The more abstract is form, the more clear and direct its appeal. In any composition the material side may be more or less omitted in proportion as the forms used are more or less material, and for them substituted pure abstractions, or largely dematerialised objects. The more an artist uses these abstracted forms, the deeper and more confidently will he advance into the kingdom of the abstract." (p. 32). This becomes his obsession, his crusade, thus he says: "Taking the work of Henri Rousseau as a starting point, I go on to prove that the new naturalism will not only be equivalent to but even identical with abstraction." (p. 52). This culminates in the final paragraph of his text: "In my opinion, we are fast approaching the time of reasoned and conscious composition, when the painter will be proud to declare his work constructive. This will be in contrast to the claim of the Impressionists that they could explain nothing, that their art came upon them by inspiration. We have before us the age of conscious creation, and this new spirit in painting is going hand in hand with the spirit of thought towards an epoch of great spiritual leaders" (p. 57). I cannot claim to be an authority on art, Russian art or Kandinsky. I have only read a few books and used my own eyes. But it does seem to me that here Kandinsky hits hubris. He has abstracted the spiritual, or so he thinks, but in the course of so doing, and doing so for all the right reasons, he has lost it. Lost connection with the "inspiration" that is of the essence of the Spirit, and instead, committed what is in technical theological language the idolatry of presuming to be in spiritual control ... complete with its "great leaders"! Light is shed on some of these issues in their wonderful Preface (Richard Stratton) and Translator's Introduction (Michael Sadler) to the text. Sadler suggests that this extreme abandonment of representation of the real world is why, "The question most generally asked about Kandinsky's art is: 'What is he trying to do?'" As he says, "this book will do something towards answering the question. But it will not do everything." (p. xviii). Cezanne, Sadler remarks, "saw in a tree, a heap of apples, a human face, a group of bathing men or women, something more abiding than either photography or impressionist painting could present. He painted the 'treeness' of the tree.... But in everything he did he showed the architectural mind of the true Frenchman. His landscape studies were based on a profound sense of the structure of rocks and hills, and being structural, his art depends on reality.... The material of which his art was composed was drawn from the huge stores of actual nature." (p. xvii). In contrast, a flick through a book of Kandinsky's work (I have been using Kandinsky (The World's Greatest Art) ) shows clearly his progressive dematerialisation, and with it, a looming nihilism. Where does all this leave us today, in 2010, 99 years after first publication of Kandinsky's little book in German? When I look at the nihilism of Britart, or the sheer inability to draw and express beauty in what seems to be coming out of some of our contemporary art schools (the students tell me they are discouraged by their tutors from trying to express beauty or to draw well), then it is clear that abstraction has become destructive. Like the postmodern deconstruction that I would see it as being cognate with, it is all very well to deconstruct, but what about the grace of reconstruction? Where the inspiration of Grace? Without it, abstraction is like the gardener who keeps pulling up the plant to see how the roots are doing. It is disincarnation, which is another word for death; a death in which the material and the spiritual wither alike because they lack mutual fecundation. The art that we need for these our troubled times needs to be an apocalyptic art in the sense of being revelatory - revealing of the lived hope that is incarnation. This will be a new art of the sacred. And here is where we need a debate to start, and artistic action around that debate. One direction might be to look afresh at Kandinsky's wonderfully expressed spiritual ideas but in the context of the Wanderers, and of contemporary wanderers. For just as the Revolt of the Fourteen was a rejection of mainstream art school narrative of its times, perhaps we need a new Revolt, and a new Fourteen, for today. In this I would urge the study by artists of a book by the theologian Walter Wink, Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination - especially the Introduction on pp. 3 - 10. Wink argues that we must reject the dualistic idea of Heaven being separate from Earth. We need what he calls an "integral worldview", what is also sometimes called an incarnational spirituality. Here Heaven and Earth are interfused in a single reality (Christians can read Luke 17:20-21; Hindus the Bhagavad Gita; Taoists the Tao Te Ching, etc.). What the world needs today to respond to the pressing issues of our times is an art that is able to "magnify" and "illuminate" the dynamics of an incarnational spirituality; ont that brings a new mind and a new heart, and gives fresh hope and vision to the world and its human condition. Kandinsky's little book provides a crucial intellectual stepping stone. But at the end of the day one has to ask if he fell off and thus, the need for a retrospective. We have lived through a century of dying and dead "modern" art. We cannot go on like that. It is time to call back the soul. I am interested in exploring that here in Govan - a hard pressed area of Glasgow - perhaps as a day conference held with local organisations and artists in 2011, the centenary of the first publication of this book. I would be interested to hear from people who might have suggestions to make about this - especially as I am not an art historian - I am a human ecologist who draws from other disciplines what is apposite to the human condition. I am also very aware that there may be people in the art colleges who are already thinking like this, marginal though such a perspective might currently be. This book review is a preliminary manifesto in that direction. As John Stuart Blackie wrote in "The Advancement of Learning in Scotland" (1855), "We demand a scholarship with a large human soul, and a pregnant social significance." May the same be considered for art.

G**I

Il testo è la testimonianza di un'epoca di passaggio, in cui il gusto estetico, l'arte, la scienza, in tutti i campi dello scibile umano, hanno raggiunto un picco. La cosa notevole di questa traduzione è che, anche se risale a più di secolo fa, è stata fatta dal suo miglior amico, e quindici è quella che rispetta megli odi ogni altra le idee di Kandinskij.

C**K

Que cosa más deliciosa de libro, bien escrito bien traducido, cada página juega con tu mente y tu espíritu

K**Y

I'm totally inlove with this book. I've read it in Spanish and English. If you want to read thoughts on art of one of the first art theoricals, this shall be it.

J**S

Kandinsky was one of the most important abstract artists. It is amazing read his words, but the print's book is horrible

Trustpilot

1 month ago

1 month ago